Parents are generally surprised when I tell them that most young people today (including their own children) are not being challenged. The surprise stems from the fact that their kids are constantly busy. They have loads of homework and tons of extra-curricular activities. How could they not be challenged?

But the fact is, having a lot to do is not the same as being stretched and stimulated by your work. Our children are busy, certainly. They may even complain about all they have to get done. But they are rarely asked to exert themselves.

I know this because they told me.

You see, after Do Hard Things came out I travelled around the country with my sons, conducting conferences for tens-of-thousands of teens, parents, grandparents, and youth workers.

At each of our conferences we provided young people with wireless keypads, which allowed them to answer questions and engage with us while we spoke. Questions appeared up on the big screen and teens were invited to choose between several options.

Here is one of the questions we asked:

Which of the following phrases best describes you?

A. Don’t care

B. Just doing enough to get by

C. Coasting

D. Exerting myself

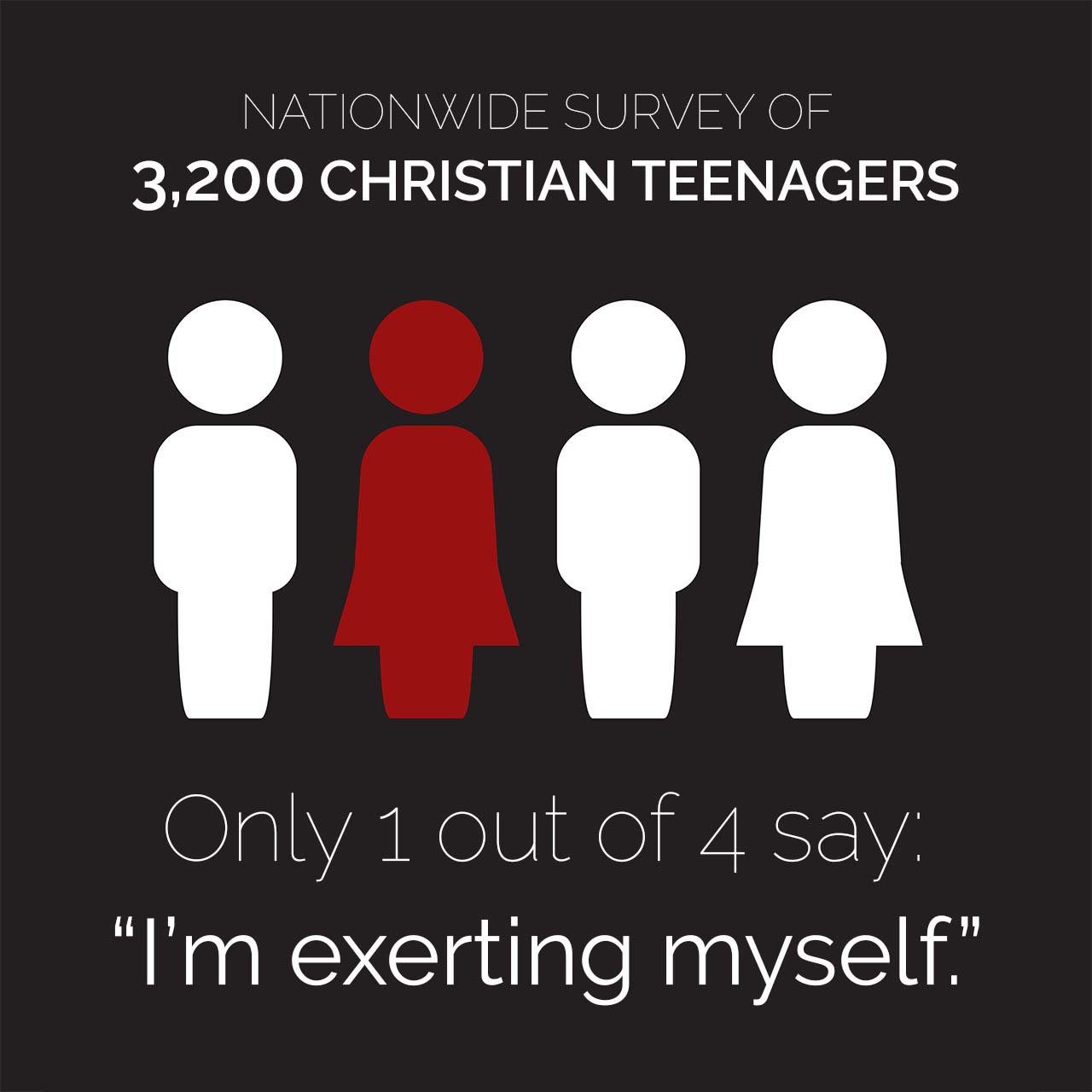

No matter where in the country we asked this question, we always received a similar result. Keep in mind that our audience was mostly composed of young people who either personally chose to attend a challenging conference or were brought by someone else. These boys and girls were more likely to push themselves or be pushed by their parents than your average youngster. As such, you’d expect a fairly high percentage to pick Option D: Exerting myself.

But here’s how the answers broke down from 3,200 students:

- 6.7% choose “don’t care”

- 23.9% choose “just doing enough to get by”

- 45.2% choose “coasting”

- 24.2% choose “exerting myself”

Everywhere we went we received the same shocking results. When able to respond anonymously using our keypads, 3 out of 4 young people would admit they just weren’t exerting themselves. Around half would acknowledge they were coasting—moving through life without effort. Only 1 out of 4 could say they were pushing themselves.

I believe this can be attributed to low expectations. Our kids, including those we’d consider exceptional, have been conditioned to go easy on themselves. They have been taught to coast.

Likewise parents, teachers, and youth workers can feel as if they are expecting a lot, when in reality they are expecting very little.

In this environment the gifted still shine, but even they are held back by low standards and the trap of being above average without trying. They are only scratching the surface of their true potential.

Tim Elmore, in a short but hard-hitting book entitled, 12 Huge Mistakes Parents Can Avoid, writes:

I believe we have under-challenged kids with meaningful work to accomplish. We have overwhelmed them with tests, recitals, and practices, and kids report being stressed-out by these activities. But they are essentially virtual activities. Adults often don’t give significant work to students — work that is relevant to life and could actually improve the world if the kids rose to the challenge. We just don’t have many expectations of our kids today. Evidently, we assume they’re incapable. Instead of rising to our expectations, they drop their heads down to send texts, play video games, scan YouTube clips, and check Facebook postings. Their potential goes untapped. A hundred years ago, 17-year-olds were leading armies, working on the farm, and learning trades as apprentices. Kids could hardly wait to enter the world of adult responsibility. That attitude is rare today.

Fortunately, the solution is simple.

We must raise our expectations. Our children don’t necessarily need more to do, but they do need more challenges. They need to do things that genuinely stretch and motivate them. They need meaningful work, not just virtual activities. They need to do hard things.

When we raise kids to do hard things we aren’t trying to make their lives busier or our own lives more stressful. Far from it! Instead we are aiming to make their lives (and our parenting) more fruitful and effective.

Are you up for the challenge?

This post is adapted from our upcoming book, Raising Kids To Do Hard Things.

Hello! This is the first post I’ve read by you and I must say that your boys are AMAZING! During the few times that we have interacted they were very kind and informative, and I ADORED that series that they did on writing and getting published since I am a young author who currently self-publishes online. And I really, really loved “Do Hard Things”. Just think, if you hadn’t given them that summer reading thingie, we probably wouldn’t have the Rebelution today!

(And now a comment that actually sticks to the topic.) I COMPLETELY agree. Most adults believe that they are placing high expectations on kids, with the testing and practices and such, but really it’s just second nature so they are not exerting themselves. In fact, as a writer I have been guilty of this, because I have often thought as I am rewriting, “This should be good enough” when in reality there is SO much more I could do to improve. My school is heavily biased towards sports, and there is so much pressure on the boys to do well, yet even though I cannot play sports (health issues) I can see some places where they could work harder.

Lastly, I hate to say this, but people tend to get offended if you say that to them. I’m not disagreeing, but that’s an observation I’ve observed.

I love how you just said one word while I just commented like an entire essay xD

Thanks for this thoughtful comment, Joye! I’m so glad you can attest to the “crazy busy but under-challenged” existence of teens today.

Also, I’m encouraged to hear that our young writer series blessed you. 😊

Oh my gosh! Hi Brett! I wasn’t expecting a reply but I am glad that you were encouraged.

Well you have done well. I wasn’t expecting you to reply at all so you have exceeded my expectations.

Would be nice to hear what would be considered challenging.

I agree with the premise of the article, but it’s frustrating to read about the problem with no solution.

I am raising 3 traumatized teens so we adopted them from the foster care system at age 9 and 10. We have followed the Do Hard Things mentality but have found that it has been impossible to get them to engage in self directed education and they do not motivate. Now we are dealing with all kinds of behaviors and are being told over and over again that we expect too much. I would agree with everything you have said about underchallenged but being able to motivate them is also a challenge if they are not willing to do the work that is needed to meet their own abilities let alone our expectations. Any words of wisdom?

Hey Crystal, I totally understand how you feel! It was not our intention to raise a problem without sharing a solution, but I see how we did that here. Part of the reason for that oversight is that we are planning to release a LOT more content for parents in the coming weeks, which will be more practical.

In the meantime, I would say that the challenges should be unique to the child — ideally related to something truly meaningful and exciting to them (i.e. self-directed, self-chosen). It should have real-world impact (in other words, other people will be affected by whether they succeed or fail). And it should push them a few steps outside their comfort zone (but not too far).

For example, my twin brother and I loved reading and my dad challenged us with a big stack of important (grownup) books to read one summer. That reading challenge resulted in us starting this website and doing conferences.

C.R. Hedgcock was challenged by her parents to write a novel and try to get it published. Now she has published an entire series of family-friendly adventure stories through Grace & Truth Publishing.

Does that help?

Hey Bethanie! First of all, Ana and I have a huge heart for foster care and are so proud of you for how you are loving these young people. The trauma and neglect they have experienced certainly “changes the rules” and makes everything more complicated.

That said, I find it hard to believe that they truly have no motivation. There’s a huge difference in whether a student can handle self-directed education (not all students can) and whether they can tackle a self-motivated, non-academic project.

My question for you would be: “What do they do when they don’t have to do anything else? How do they spend their free time? What do they enjoy?”

Don’t filter the answers according to what activities you believe are worthwhile. If it’s skateboarding, then it’s skateboarding. If it’s video games, then it’s video games.

The reality is, most people don’t just sit around in a coma in their free time. They have interests. They have things they are self-motivated to pursue. And any activity that is not inherently sinful can be harnessed to teach the habit of self-motivation and help students develop portable skills that will serve them later in life.

For example, at one point my little brother Isaac was into airsoft. It’s sort of like paintball, except the guns shoot little plastic pellets. Rather than squash that interest because it had no future, my parents encouraged him to organize an airsoft war on our property. He was 12-years-old and came up with rules, divided teams, made sure everyone had pellet guns and ammo, cleared trails through the woods, made phone calls, and created spreadsheets.

Today Isaac’s airsoft gun collects dust in a closet, but the leadership skills and other portable skills he developed through that season are still serving him today.

Hope that helps a little!

Haha! Yep! Time for Brett to cuff me and send me to low expectations jail. (Hard things currently doing: reading the Bible daily, juggling an AP class and keeping me math grades up, and trying to finish my book)

What? Lol

Lol.

WOW! #speechless